The Futility Infielder

A Baseball Journal by Jay Jaffe I'm a baseball fan living in New York City. In between long tirades about the New York Yankees and the national pastime in general, I'm a graphic designer.Thursday, September 17, 2009

One for the Ages

— Maxwell Scott, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance

That Satchel Paige was one of the greatest baseball players of all time isn't exactly a controversial topic these days. Even casual fans are probably familiar with the colorful Paige's aphorisms ("Don't look back. Something might be gaining on you"), and have some understanding not only of how brightly he shone amid the high-caliber talent which was so cruelly deprived of the opportunity to play major league baseball by the game's segregation, but also the fact that even a forty-something-year-old version of the pitcher found success at the major league level once Jackie Robinson shattered the color barrier. It's certainly a tale worth telling and retelling, though as engaging as the oft-repeated lore surrounding the pitcher's career and character is, repetition has tended to distort and oversimplify the truth about him.

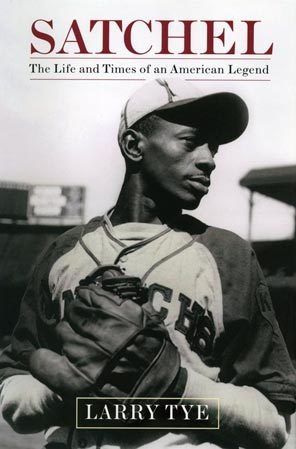

Luckily, Larry Tye has come along to boldly confront the myths surrounding Paige in an excellent new biography, Satchel: The Life and Times of an American Legend. I received a copy in the mail several weeks ago and had been itching to dive into its pages before finally getting an opportunity during my recent trip to Buenos Aires.

Many of those myths surrounding Paige, of course, were of the pitcher's own making via interviews and as-told-to autobiographies, and they were a crucial part of his public relations strategy. In his preface to the book (published as an excerpt at Bronx Banter), Tye explains Paige's obfuscation about his birthdate:

Satchel knew that, despite being the fastest, winningest pitcher alive, being black meant he never would get the attention he deserved. That was easy to see in the backwaters of the Negro Leagues but it remained true when he hit the Majors at age forty-two, with accusations flying that his signing was a mere stunt. He needed an edge, a bit of mystery, to romance sportswriters and fans. Longevity offered the perfect platform. "They want me to be old," Satchel said, "so I give 'em what they want. Seems they get a bigger kick out of an old man throwing strikeouts." He feigned exasperation when reporters pressed to know the secret of his birth, insisting, "I want to be the onliest man in the United States that nobody knows nothin' about." In fact he wanted just the opposite: Satchel masterfully exploited his lost birthday to ensure the world would remember his long life.While Tye digs deep — the book's bibliography and end notes are both at least 35 pages long, and he interviewed more than 200 Negro League and major league opponents and teammates — and lays waste to some of the tall tales surrounding Paige, what emerges is an altogether more nuanced and ultimately more compelling version of the ageless pitcher. Some of Paige's embellishments, such as his account of his pitching the championship finale for Dragones de Ciudad Trujillo in the Dominican Republic in 1937, don't stand up to the light of day. Others, such as the masterful control which allowed him to throw the ball over a chewing gum wrapper with amazing consistency or his brazen penchant for calling in his outfielders and then getting the crucial strikeout(s), he finds well-documented.

It was not a random image Satchel crafted for himself but one he knew played perfectly into perceptions whites had back then of blacks. It was a persona of agelessness and fecklessness, one where a family's entire history could be written into a faded bible and a goat could devour both. The black man in the era of Jim Crow was not expected to have human proportions at all, certainly none worth documenting in public records or engraving for posterity. He was a phantom, without the dignity of a real name (hence the nickname Satchel), a rational mother (Satchel's mother was so confused she supposedly mixed him up with his brother), or an age certain ("Nobody knows how complicated I am," he once said. "All they want to know is how old I am."). That is precisely the image that nervous white owners relished when they signed the first black ballplayers. Few inquired where the pioneers came from or wanted to hear about their struggles. In these athletes' very anonymity lay their value.

Playing to social stereotypes the way he did with his age is just half the story of Satchel Paige, although it is the half most told. While many dismissed him as a Stepin Fetchit if not an Uncle Tom, this book makes clear that he was something else entirely – a quiet subversive, defying Uncle Tom and Jim Crow. Told all his life that black lives matter less than white ones, he teased journalists by adding or subtracting years each time they asked his age, then asking them, "How old would you be if you didn't know how old you were?" Relegated by statute and custom to the shadows of the Negro Leagues, he fed Uncle Sam shadowy information on his provenance. Yet growing up in the Deep South he knew better than to flaunt the rules openly, so he did it opaquely. He made his relationships with the press and the public into a game, using insubordination and indirection to challenge his segregated surroundings.

As always, there are the quotes, most of which really did come out of Paige's mouth in some form or other. Asked by his manager if he threw fast consistently, he replied, "No sir, i do it all the time." Asked about his philosophy of pitching, he warned, "Bases on balls is the curse of a nation... throw strikes at all times. Unless you don't want to." Of course, it's interesting to learn that the six rules for staying young for which he's credited were partly the work of Collier's Richard Donovan, as the sidebar to a three-part profile from 1953. And, as Tye notes, not always taken to heart by the font of wisdom from which they supposedly flowed.

Through it all, Tye meticulously tracks Paige's peripatetic ways, noting not only his myriad stops both on his way up (he began pitching professionally in Chattanooga in 1926) and down (his last major league appearance was with the Kansas City A's in 1965; his last regular duty was with the Triple-A Miami Marlins from 1956-1958) but also his numerous barnstorming tours, not to mention the countless times he jumped teams to collect a bigger payday, often by less-than-honorably walking out on his contract. The book's appendix even has a well-compiled statistical thumbnail, collecting the best-researched data on Paige's time in the Negro Leagues, majors, minors, East-West All-Star Games, North Dakota, California Winter League and Latin leagues (though it misses two late stints in the minors in Portland and Hampton, Virginia).

The author offers a good deal of insight into the conditions Paige played under and the men he played for, such as Pittsburgh Crawfords owner Gus Greenlee and Kansas City Monarchs co-owner J.L. Wilkinson (whose business partner, Tom Baird, was a member of the Ku Klux Klan). If I have a quibble about the book it's that he doesn't go into great enough detail about many of the men he played with and against, particularly Josh Gibson, though the portraits of barnstorming rivals Dizzy Dean and Bob Feller do stand out. He's acutely aware of the generation gap between Paige and Robinson, or Paige and Indians teammate Larry Doby, who broke the American League color line in July 1947, and doesn't sugarcoat Paige's mixed emotions at being passed over as the man to break the majors' color barrier.

In all, Tye's created an impressive work that never feels bogged down by its lofty ambitions or the weight of the author's research; his prose is a breeze, for the most part. He makes a convincing case for Paige not only as one of baseball's all-time greats but as an agent of social change, covering seemingly millions of miles as he lay the groundwork for the game's integration, delighting fans and winning over doubters and even the occasional bigot while building a legacy that might be matched only by Babe Ruth's in its importance to the game and the nation. This one's a keeper.

For more about the book, see Tye's web site.

Labels: baseball history, books

Archives

June 2001 July 2001 August 2001 September 2001 October 2001 November 2001 December 2001 January 2002 February 2002 March 2002 April 2002 May 2002 June 2002 July 2002 August 2002 September 2002 October 2002 November 2002 December 2002 January 2003 February 2003 March 2003 April 2003 May 2003 June 2003 July 2003 August 2003 September 2003 October 2003 November 2003 December 2003 January 2004 February 2004 March 2004 April 2004 May 2004 June 2004 July 2004 August 2004 September 2004 October 2004 November 2004 December 2004 January 2005 February 2005 March 2005 April 2005 May 2005 June 2005 July 2005 August 2005 September 2005 October 2005 November 2005 December 2005 January 2006 February 2006 March 2006 April 2006 May 2006 June 2006 July 2006 August 2006 September 2006 October 2006 November 2006 December 2006 January 2007 February 2007 March 2007 April 2007 May 2007 June 2007 July 2007 August 2007 September 2007 October 2007 November 2007 December 2007 January 2008 February 2008 March 2008 April 2008 May 2008 June 2008 July 2008 August 2008 September 2008 October 2008 November 2008 December 2008 January 2009 February 2009 March 2009 April 2009 May 2009 June 2009 July 2009 August 2009 September 2009 October 2009 November 2009 December 2009 January 2010 February 2010 March 2010 April 2010 May 2010

Subscribe to Comments [Atom]