The Futility Infielder

A Baseball Journal by Jay Jaffe I'm a baseball fan living in New York City. In between long tirades about the New York Yankees and the national pastime in general, I'm a graphic designer.Thursday, May 29, 2008

Miller Time

I'd already written the bulk of a piece about Miller's odd request when, at the encouragement of Alex Belth and Allen Barra, both of whom I'd consulted for some background for the piece, I did something I rarely do, something I need to do more often: pick up the damn phone and go to the source. Miller is completely accessible, listed in Manhattan's white pages, and while he's physically frail, he's sharp as a tack, mentally. Despite the dour subject matter -- we did discuss the man's posthumous wishes, after all -- ours was a delightful conversation. I had trouble getting a word in edgewise during the first six or seven minutes as he laid out his history with the Hall, but by the end we were sharing laughs, and Miller made my head swell when he paid my previous writing about him a compliment.

Anyway, the article is today's freebie at Baseball Prospectus; a full transcript of our conversation will run in the near future:

The Hall of Fame was in the headlines last week, and not just because the retirement of Mike Piazza kindled the inevitable debate over his Cooperstown credentials. No, an even more deserving honoree made waves via what was almost certainly a first: a request to the voters not to be elected.Thanks to Barra, Belth, and of course Miller for their cooperation and encouragement with this article. While I think the Hall of Fame is a lesser place without Miller and part of me hopes that someday this sorry chapter ends with his induction, I admire his chutzpah for speaking up. His place in baseball history is already guaranteed with or without the sanctioning of Cooperstown's cronies, and his actions expose major cracks in the Hall's foundation, cracks that the institution would do well to address while the men it should be honoring are still alive to enjoy their glory.

The unusual appeal came from Marvin Miller, who served as the executive director of the Major League Baseball Players Association from 1966 to 1982, overseeing baseball's biggest change since integration via the dismantling of the Reserve Clause and the dawn of free agency. Snubbed by an ever-changing electoral process three times in the past five years, the 91-year-old Miller is not only tired of his hopes being dashed, but disillusioned with the institution itself. "As I began to do more research on the Hall, it seemed a lot less desirable a place to be than a lot of people think," said Miller in a recent interview with Baseball Prospectus. "Some of the early people inducted in the Hall were members of the Ku Klux Klan. Tris Speaker, Cap Anson, and some people suspect Ty Cobb as well. When I look at that, and I looked at the more current Hall, it was about as anti-union as anything could be," he continues, citing recently ousted Hall president Dale Petroskey's past service in the union-busting Reagan White House. "I think that by and large, the players, and certainly the ones I knew, are good people. But the Hall is full of villains."

...It's unclear whether the Hall will honor Miller's wishes. President Jeff Idelson--who took over in late March after Petroskey resigned--believes the VC will again be reconstituted before the next vote. He says that the institution plans to discuss the matter with Miller, and that while his request will be communicated to the screening committee, there's no guarantee his wish will be heeded; Miller will be nominated if the committee so decides. That reaction suggests Miller's statement may work as a bit of reverse psychology -- if he's daring the electorate not to tab him, what better way to piss the man off?

Miller is hardly waiting for the Hall's overtures. He sounds genuinely at peace with his own intractability on the matter, invoking an unlikely pair of historical figures in Civil War General William Tecumseh Sherman and comedian Groucho Marx. "[Sherman] basically said, 'I don't want to be president. If I'm nominated I will not campaign for the presidency. If despite that I'm elected, I will not serve.' Without comparing myself to General Sherman, that's my feeling. If considered and elected, I will not appear for the induction if I'm alive. If they proceed to try to do this posthumously, my family is prepared to deal with that."

The mention of Marx adds a final bit of levity to Miller's request. "What [Marx] said was words to the effect of, 'I don't want to be part of any organization that would have me as a member.' Between a great comedian and a great general, you have my sentiments."

Labels: baseball history, Hit and Run

Tuesday, May 27, 2008

Bernard Jaffe: a Centennial Celebration

Bernard -- "Bernie" or "BJ" to friends, "Poppy" or "Pop" to me -- was a lifelong baseball fan who witnessed a marvelous swath of baseball history over his 92 years of life. When I was a youngster, he regaled me with tales of seeing the "Murderer's Row" Yankees of Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, Giants such as Mel Ott and Bill Terry, and the daffy Dodgers, who became his team after he watched star outfielder Babe Herman get hit on the head with a fly ball he was attempting to catch. To him, the underdog and occasionally hapless Bums of Brooklyn offered an appeal that the Giants, class of the National League for so many years, couldn't match. Even after departing Brooklyn to move across the country more than a decade ahead of the Dodgers, he passed on his allegiance to his sons and grandsons.

I was Pop's first grandchild, and I believe he always found something in me that he could connect with. While fully capable of being outgoing, both of us at heart were introverts, and we shared a similar love for reading. In addition to his oral history lessons, Pop encouraged me to read about the game, and not just via the pallid biographies written for kids. I vividly remember the day a box of secondhand paperbacks he'd rescued from the flea market arrived at my Salt Lake City home. At nine years old, I was reading Roger Angell's erudite essays in a dog-eared copy of The Summer Game and parsing the more complicated swear words in a musty edition of Jim Bouton's Ball Four. Those two books in particular introduced a self-awareness which shaped my powers of observation and eventually, my writing while rendering schoolboy fare like All-Pro Baseball Stars 1979 obsolete.

• • •

Born in Brooklyn on May 20, 1908 as the third of four boys, Pop rarely spoke his childhood, which wasn't the happiest. His father was a master tailor and a rabble-rouser who at various times in his career was blacklisted because of his efforts to unionize the garment factories in which he worked. Emotionally, he was a cold man, who didn't provide much overt affection. From what I understand, at some point he walked out on his family, though it wasn't until later that he obtained a divorce and remarried. Though I'm sure the era had something to do with the way he was raised, Pop took the counter-example of his own life to heart; he was a warm, generous, devoted family man and a pillar of his community.

This is him as a young boy, with mother Dora on the left, c. 1915:

Though only a wiry 5-foot-8 1/2, Pop was an excellent athlete. He played baseball at the University of Maryland, and was said to have been offered a professional contract by the Washington Senators, but he had other ideas about what he wanted to do in life. He got a graduate degree as a pharmacist, and worked for six months in Baltimore while hustling pool at night to help save up enough money to attend medical school. Unable to afford the exorbitant cost of attending a stateside medical school, and stymied by the quota system which limited the number of Jews, he managed to start his studies in -- of all places -- Hitler's Germany, at the University of Göttering (sp?). The chutzpah! He didn't know much German when he came over, but he learned the language by reading newspapers and walking the streets. He somehow managed to wrangle a ticket to the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, where he saw Jesse Owens show up Hitler by winning four gold medals.

Standing to the left of brothers Hank and Matty, this picture shows Pop in a rather streetwise pose, as though waiting for his next mark to show up to the pool hall. It's dated 1936, but I believe it's a bit earlier, from before he went overseas:

After a year at Göttering, he was advised to leave, and he transferred to the University of Vienna, where he met Clara Gottfried (1912-2006), a woman four years his junior but a year ahead of him in medical school ("Nanny" or "Nan" to me). They met one Saturday night while she was studying for an exam in a coffee house; he was playing pool, saw and recognized her, and offered to walk her home. They married in Vienna on March 29, 1938, and with the situation there worsening vis-à-vis the Nazis, began planning their exit. When he finished his studies, Bernard didn't even wait around to receive his diploma; a classmate named Dr. Samuel Schoenberg picked it up along with his own, and escaped by walking over the Alps into Switzerland.

Bernie and Clara in Vienna, 1938:

Thanks to the efforts of an American cousin of her father named Marcus Helitzer (who opened an American bank account in her name with $1,000), Clara was granted a visa to travel to the US. The couple booked passage on a ship and arrived in the US on July 15, 1938, but Clara never saw her parents again. Both died in concentration camps, as did nearly all of my grandmother's relatives.

Stateside, my grandparents settled in New York City. Bernard got an internship at Brooklyn Lutheran Hospital, living on hospital grounds while Clara lived out on Long Island with the Helitzer family, and they saw each other on weekends. She got a job working as the physician for a girls' camp in Liberty, New York, and soon earned enough money to get an apartment of her own on 86th Street. He entered the Army Reserves in 1939, and she took over his internship, having passed her medical boards in April.

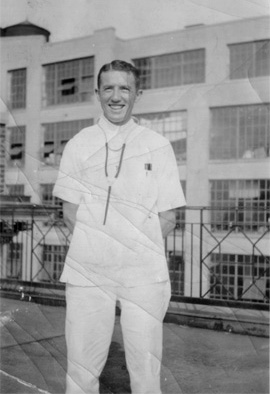

What's up, Doc? Bernie on the grounds of Brooklyn Lutheran in 1939:

When Clara completed her internship, Bernard asked her to join him down in Asheville, North Carolina, where he was the physician at a Civil Conservation Corps base. In those uncertain times, he wanted her to settle down and to start a family. He got his first position in Hot Springs, outside of Asheville. When the Reserves called him up for active duty, he failed his physical. The story goes that he'd been playing tennis and, not having a car, had run several miles to the offices. When he arrived, he was sweating profusely. The doctor asked if this happened often, and when he said yes, the doctor feared he had a cyst. He was turned down for active duty and sent to Augusta, Georgia to train for the Veterans Administration hospital. There, my father (Richard) was born in 1941.

Bernie and Clara, 1940 in Miami:

With my dad at about one year old, 1942:

They bounced around -- the life of an Army doctor -- finally settling in the farming town of Walla Walla, Washington in 1944; they had another son, Bob, in 1946. While my grandmother adapted to life as a homemaker, my grandfather made his practice as an otolaryngologist (ear, nose and throat doctor), and practiced at the VA hospital there until his retirement in 1973. Upon leaving the VA grounds, they bought a house at 1966 Scarpelli, and he lived out the rest of his life there. When he retired at age 65, Pop didn't think he had many years left to live; the average life expectancy at the time was only about 73 years old. Instead he managed to live another 27 years, long enough to see all four of his grandchildren grow into early adulthood.

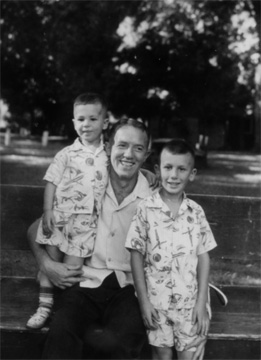

With both of his kids, 1949:

• • •

I spent many a wonderful summer day with Nan and Pop. They would drive down to our home in Salt Lake City, and after a visit of about a week, would drive us back to Walla Walla; Pop would his massive gas-guzzler (a Cadillac Seville, I think) drive the entire distance in one 12-hour day, and we'd stop for dinner at Sizzler about an hour or so outside of town. We'd spend as long as three weeks in Walla Walla, then my parents would meet us there or we'd rendezvous at a family reunion on the Oregon coast or at the Black Butte Ranch, near Sisters, Oregon.

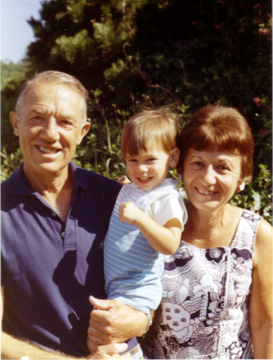

With their first-born grandson (me), 1971:

Pop gave me my first ball glove, an occasion that remains etched in my memory, a warm summer evening when I was about seven. Instead of playing whiffle ball in the backyard as we regularly did with my father, my brother and I were instructed to put the mitts on our left hands. We struggled to grasp this fundamental puzzle just as surely as we did the balls Pop and Dad lobbed to us from a few paces away, but gradually we got the hang of it.

Dad usually had time to play catch or Hot Box with my brother and me on a regular basis, but when we stayed with my grandparents, we were in baseball immersion camp. In the morning Pop and I would walk down to the grocery store to get the morning paper, The Oregonian, and we'd read the boxscores and game summaries on the way home. After that we'd collect my brother and go to nearby Howard Tietan Park, where Popwould pitch to us from behind home plate as we'd smack balls, five a turn, into a backstop where one rung meant a single, two a double, three a triple, and over the backstop a home run (just this past winter I discovered that this was actually an old stickball variant). When the balls got too beat up from bashing into the chain links of the backstop, Pop covered them in electrical tape and we'd hammer them until they resembled squeezed grapefruits.

We'd also play catch in his endless backyard; he'd throw long balls and we'd chase after them, laying out for "spectacular catches," the name we gave that particular drill. We'd play in his huge garden; while he would spend endless hours picking enormous raspberries (which Nan would turn into delicious jams), we'd throw the various fallen fruits and vegetables into an oversized barrel of dirt and compost which we called "elephant stew." In the evening we'd watch baseball on his new-fangled cable TV system, which included the fledgling ESPN station. My brother and I would sit on the arms of Pop's big red leather chair. Often he'd turn the volume down and play classical music while talking to us as the game went on, perhaps breaking out a crossword puzzle, a favorite pastime, and pitching us the easy clues while explaining the harder ones in an effort to expand our vocabularies.

Once in awhile, we'd go see the Walla Walla Padres, the Low-A Northwest League affiliate of San Diego, play at Borleske Stadium. I watched a handful of players who would leave their marks in the majors in some way or another come through Walla Walla, including Tony Gwynn, John Kruk, Mitch Williams, Jimmy Jones, Kevin Towers, Greg Booker, and Bob Geren. The league featured opponents like Mark Langston and Phil Bradley of the Mariners' Bellingham squad as well. Even then I kept score at those games, and I still have the those programs. In the summer of 2006, I served as the consultant for a bobblehead commemorating Gwynn's 42-game stay with Walla Walla in 1981, to be issued the following year in celebration of his induction into the Hall of Fame.

As I got older, the visits to Walla Walla inevitably stopped; the last year I recall us staying with them was 1982, which as it turns out was also the last year the Padres were in town. In retrospect, I realize how lucky my brother and I were to share so much time with my grandparents; my cousins, who are five and seven years younger and lived much closer in Seattle, didn't get the same mass quantity of quality time, didn't know them in the same way.

We still saw Nan and Pop a couple times a year in Salt Lake City, and talked on the phone every couple of weeks. Every so often, another box of books would arrive, more baseball to bind us together. The calls grew less frequent as Pop's hearing seriously declined; he never really adjusted to wearing a hearing aid, often turning the accursed thing off and missed out on a lot of the conversation. Nonetheless, he was still pretty sharp into his late 80s; not until various physical maladies, including prostate cancer, began taking their toll did the quality of our conversations really take a downturn.

I last saw my grandfather in 1999, when I visited Walla Walla with my parents. He was frail, stooped, and using a walker, a shadow of the vital man I'd once known. I recall that we watched a few innings of a ballgame together, seeing the Yankees' Orlando Hernandez get knocked out of the box against the Mariners in newly-opened Safeco Field. Later that day, he gave me a prized possession I knew had been coming my way for quite some time, a vintage Rolex watch that he'd owned for 50 years, squirreling away for a day when he cold pass it on. It's a beautiful, timeless timepiece; I still think of him every time I wear it.

Pop passed away quietly on November 24, 2000, the day after Thanksgiving. I flew to Walla Walla and joined my father, uncle and brother in delivering eulogies and serving as a pallbearer. My grandmother would survive until August 2006, sharp into her early 90s; I wrote about her passing here.

• • •

Four and a half months after Pop passed away, one of my baseball favorites, Willie Stargell, died as well, and it brought back a flood of memories of Pop, Bryan and I watching the 1979 "We Are Family" Pirates, who were all over the airwaves that summer on their way to a World Championship (the Dodgers, coming off consecutive pennants, were stuck in sub-.500 oblivion). Moved by Stargell's passing and, in the tradition of my grandfather, struck with a yearning to pass on a generation of baseball wisdom to those whose appreciations didn't go back as far, I wrote an obituary of sorts, and emailed it around to friends. It became the cornerstone of the Futility Infielder website.

In two weeks time, I'd registered a domain name, opened a Blogger account, and bought a book on web site design. The rest is history, my history. For as much as I was able to glean from my grandfather, there are many times I've found myself wishing he'd kept a memoir of the players and the games he saw. They would have provided me more insight into the man, as well as those times, and his keen eye and dry wit would have been preserved for posterity. So it is that I record my own thoughts and descriptions in the hope of sharing my interest in the Mendoza Line, the 1998 Yankees, and the games of today. The arcane and the amazing as well as the now, a flowing river of baseball history that began with a man born a century ago.

Labels: non-baseball, passings, Walla Walla

Sunday, May 25, 2008

They're Playing Our Song

A dismal week for the Yankees ends on a high note with the return of Alex Rodriguez (4-for-11 with two doubles and two homers after a 17-game absence) and strong performances from Darrell Rasner and Ian Kennedy. The former puts together his third straight quality start, lowering his ERA to 1.89, while the latter finally gets his ERA down to Boeing territory (7.27) with just his second quality start out of seven. More help is on the way for the Yanks, who begin Joba Chamberlain's conversion to the rotation; while the move will be second-guessed by some wags, the Yanks simply need him there; their rotation is 10th in SNLVAR and last in innings pitched per start, while the bullpen is seventh in WXRL.The Yankees kept the good times rolling after that was published on Friday, rolling up 13 runs against the hapless Mariners, and the line kept moving on Saturday, when I took my in-laws to Yankee Stadium for the first time and watched the Yankees continue to treat the Mariners like a punching bag as they won 12-6, their fourth victory in a row. It was a gorgeous day, sunny and in the high 60s, and for a Saturday it wasn't so crowded as to be claustrophobic, thanks to the opponent and the holiday weekend. A great day for baseball.

Nonetheless, the day wasn't without its disappointments even from the get-go. Upon arriving at the park at 11:45 AM, we were shut out of a chance to see Monument Park; according to the math of the security thug's claim, the line had closed ten minutes after the stadium opened, ha ha ha. Despite having bought tickets via an Internet pre-sale for ticket-package holders back in February, the best I had done for four seats while still having enough money left over to make the mortgage payment was in Section 36 in far left field, over 400 feet from home plate and just a few seats from the edge of the stadium -- further than a man with eyesight as bad as mine (not to mention the occasional touch of vertigo) should sit if he wants to pay attention.

Still, my in-laws, who hail from Milwaukee and are well-versed with the quaint amenities of Miller Park, were in awe of the old ballpark. We practically circled the stadium twice, once at field level -- I got them as close to the monuments as I could, and they saw the dying embers of batting practice as well -- and then once at the upper level, where they got a great view of the new park under construction.

Our final location did afford us a pretty good view of the long fly balls the Yankees walloped all afternoon, including Jason Giambi's three-run homer to left-center field, part of a four-run second inning at the expense of Mariner starter Carlos Silva. Giambi had three hits on the day, two to the left side, and he looks locked in; his low batting average (he started the day at .217) disguises the fact that he's hitting .386/.509/.773 over his last 14 games. Bobby Abreu cracked a homer and drove in four runs, Robinson Cano went 4-for-4 (he's hitting .375/.412/.578 since May 4), and every batter in the lineup except Derek Jeter got a hit.

From our perch, which overlooked both bullpens, we also got to see and hear Joba Chamberlain warm up, which required me to give my in-laws a patient explanation both of the pitcher's phenomenal ascent and the controversy surrounding his usage. Mike Mussina had quickly squandered the 4-0 lead, giving up a three-run homer to slumping Jose Vidro in the third and then a solo shot to Adrian Beltre two batters later, but the Yanks rallied for a run in the bottom of the inning and the Moose slogged through five innings before departing with a 5-4 lead. Chamberlain, scheduled to pitch as the Yankees continue the process of stretching him out for the rotation, began warming up in the fifth, creating a resounding pop every time he hit the catcher's mitt with his fastball. He came in and struck out two hitters in the sixth, then pitched into and out of trouble in the seventh. In all, he threw 40 pitches, five short of his target for the day, but he looked pretty good.

While there was plenty to cheer about, the day's biggest downer came from a trio of 40-something jackasses sitting in front of us and virtually ignoring the five-year-old son of one of the men. The little boy, wearing a yellow tee-ball t-shirt, was seated on the end of the row, right next to the railing and isolated from the attention of his father and the rest of the group. That was probably just as well, given that the topics of their conversation -- spoken loudly enough that anyone within 15 feet was well-apprised of their thoughts on anything, and sprinkled with more than enough "shits" and "fucks" than anyone, let alone a five-year-old needed to hear -- included choosing strip clubs, going to strip clubs, being at strip clubs, the efficacy of the old "hair of the dog" hangover treatment, pounding beer, pounding more beer, getting a drivers licence reinstated after a DUI, tattoos (one guy had a giant scorpion wrapped from his lower back over his shoulder and to his chest), spoiled kids, the ineptitude of the Devil Rays (this said by the one of the group who was visiting from Tampa, clearly not paying much attention these days), and this country's propensity for military action. "Name me one fucking year since 1960 that this country hasn't been at war," challenged the history professor from Tampa, who apparently had promised to serve as the designated driver, having curbed his drinking maybe an inning before last call. Yeesh.

Not even those assclowns could ruin our day, not with the weather, the company and the results all working in our favor. The in-laws enjoyed the various rituals of Yankee Stadium, including the groundskeepers' "Y-M-C-A" motions after the sixth, "Take Me Out to the Ballgame" in the seventh, and "New York, New York" after the final out. That moment was curiously delayed when the home plate ump, apparently trying to make a quick getaway, called Beltre out on strikes at just strike two, triggering the Sinatra song. Confusion reigned on the field, as puzzled Yankees began congratulating each other before order was restored. With the crowd seeemingly all standing in the aisles or on the concourses in anticipation of the game's official end, Beltre lasted five more Mariano Rivera pitches before grounding out to Cano. Finally, they were playing our song.

Labels: game reports, Hit List, Yankee Stadium, Yankees

Thursday, May 22, 2008

Cubs' Chances and Chamberlain's Change of Pace

It's been a rough century for the Cubs. They haven't won a World Series since 1908, and they haven't captured a pennant since 1945 despite the best efforts of superstars like Ernie Banks, Ryne Sandberg, and Sammy Sosa. They've punctuated that dry spell with agonizing collapses — their late-season fade in 1969, a squandered 2-0 lead in a best-of-five Championship Series in 1984, and the Steve Bartman debacle in 2003 — and watched as the Red Sox and crosstown White Sox have overcome similarly epic championship droughts. History has not been kind, but at long last, this may finally be the Cubs' year.The race appears tight at the moment, but the two teams hanging with the Cubs, the Cardinals and Astros, were forecast for just 75 and 72 wins, respectively, and the adjusted run differentials suggest a three- and five-game gap between the Cubs and those two teams. Meanwhile, the Brewers, who were forecast for 86 wins, appear dead in the water at the moment, their bullpen frightful and their rotation depth squandered. So my money's on the Cubs.

On the surface, the team simply appears to be solid contenders, perhaps a bit improved off of last year's NL Central-winning 85-77 record. Their two-game lead in the division isn't overly generous, and at 28-18, they trail the Diamondbacks by half a game in the race for the league's best record. However, thanks to a recent 9-2 tear in which they outscored opponents 67-35, they have the majors' best run differential through Tuesday, at +76 runs. It's not like they're playing far above their heads, either. This spring, Baseball Prospectus' PECOTA forecasting system tagged the Cubs for 93 wins, tops in the division and second only to the Mets among NL teams.

Leading the way for the Cubs is an offensive juggernaut that's scoring a major league-best 5.7 runs per game while hitting .285 AVG/.371 OBP/.448 SLG, tops the NL in the first two categories, and second in the latter. Left fielder Alfonso Soriano has powered the recent streak with a 21-for-44 tear that included seven homers in six games, but he's had plenty of help. Indeed, the Cubs are getting above-average production at every position except center field, with first baseman Derrek Lee, second baseman Mark DeRosa, third baseman Aramis Ramirez, right fielder Kosuke Fukudome, and shortstop Ryan Theriot all getting on base above a .400 clip.

On-base percentage is the offensive statistic which best correlates with run scoring, and historically, it's been an Achilles heel for the Cubs. Former manager Dusty Baker showed a maddening tendency to favor free swingers over disciplined hitters; as a result, the Cubs never placed higher than 11th in OBP during his four-year tenure (2003-2006), but it wasn't all Baker, as the problem goes back much, much further. The team hasn't led the league in OBP since 1972, and has only placed in the top three four times - 1972, 1975, 1984 and 1989, the latter two playoff seasons - since 1945, when the club ranked second.

Under new skipper Lou Piniella, last year's unit ranked ninth in the league with a .333 OBP, up from a dead-last .319 mark in Baker's final year. This year's offense has been bolstered by the additions of Soto, a top catching prospect who hit a searing .353/.424/.652 at Triple-A Iowa last year, and Fukudome, an import who topped a .430 OBP in the Japanese Pacific League in each of the last three years while drawing comparisons to Bobby Abreu and J.D. Drew for his moderate power/high-OBP skill set.

Meanwhile, I missed Tuesday evening's Yankee debacle but caught some of last night's rout, when recently returned Alex Rodriguez turned Yankee Stadium into his own personal pinball game, going 3-for-4 with two doubles and a homer, a tally that should have been the other way around were it not for a blown home run call, the second in a Yankees game this week. Bigger than that, however, was the fact that Joba Chamberlain threw two innings of scoreless ball to close out Darrell Rasner's fine seven-inning shutout effort. According to Brian Cashman, Chamberlain is beginning the process of being stretched out to join the rotation. Amid all the misdirection the Yankees have been running on this, I'm going to claim victory for having anticipated this the last time I wrote about the pinstripes and talking about it during my two radio hits yesterday. In some quarters this may be spun as a panic move, a reaction to Hank Steinbrenner's recent outbursts, but this isn't Cashman's first rodeo. The math regarding Joba's innings pace suggests that this was the plan all along. Pete Abraham, who agreed with that assessment when I bounced it off him this past weekend, has a trio of good blog entries covering the angles related to this move. Go.

The Hit List beast beckons...

Labels: New York Sun, Yankees

Wednesday, May 21, 2008

Three Things

• • •

Mike Piazza retired on Tuesday, ending a stellar 16-year career which saw him make the All-Star team 12 times and finish with a lifetime .308/.377/.545 line and 427 home runs. A fellow Dodger fan came asking about his Hall of Fame credentials on Tuesday evening, prompting me to put together a quick piece for Baseball Prospectus Unfiltered. The bottom line is that Piazza's JAWS score inches past the Hall of Fame standard for catchers on the basis of his strong peak, but that's not the most interesting part of the story:

Bolstering Piazza’s primary JAWS case are his secondary numbers, which confirm the oft-repeated claim that he’s the best-hitting catcher of all time. Piazza’s .311 EqA [Equivalent Average] is the all-time high for the position. No Hall of Fame catcher has an EqA above .300, though there are several in the .295-.299 range and the positional average is a robust .289. The highest EqA for a catcher not in the Hall of Fame is sabermetric hero Gene Tenace at .308 (ayyy Gino!), while the highest active marks coming into 2008 were held by Joe Mauer (.305) and Jorge Posada (.300).Piazza also holds the record for home runs as a catcher, hitting 396 of his shots while playing that position. His fielding is another story; at -149 runs, he's the worst-fielding catcher ever, which prevents him from topping the JAWS list at his position. Had he taken the time to learn first base in his later years, he might have had a shot at 500 homers, but as it is, he's still got enough of the good stuff for the Hall of Fame.

Furthermore, Piazza’s 472 Batting Runs Above Average is light years ahead of the rest of the backstop pack. No Hall of Fame catcher has more than Johnny Bench’s 325 BRAA. Joe Torre, at 396, is the only hitter between Bench and Piazza, and while he played a plurality of his games at catcher (893) and this is classified as such in our system, the majority of his time was actually split between the infield corners (793 at first base, 515 at third). Torre’s got a lifetime .298 EqA as well.

As I discussed in the piece, his final game at Shea, as a member of the Padres, was a night to remember. No matter what uniform he wore, he was always something to behold as a hitter, and he'll be missed.

• • •

The transcript for yesterday's BP chat can be found here. The Cubs, about whom I spent a good portion of the day working on a forthcoming piece for the New York Sun, were a popular topic, as were the Dodgers -- particularly regarding the news that Andruw Jones has torn cartilage in his right knee -- and the Yankees, whose season continues to spiral downward:

scareduck (Still closer to Angel Stadium than Chavez Ravine): Three questions: 1) For my Cubs lovin' wife, are the Northsiders for real? They've done well so far, but what are their big questions down the stretch? 2) Is there any light at the end of the Andruw Jones tunnel, or is that the sound of a diesel locomotive? 3) Joe Torre: great manager, or *greatest* manager? Seriously, look at Friday's Dodgers lineup: how could he expect to win?That's Rob McMillan in the top spot above, operator of the Dodgers- and Angels-themed 6-4-2 blog, which is one of my daily reads, incidentally. Anyway, I had some great chat questions left over, enough that I may repurpose some of them into my next Hit and Run column. Like a good chef, I do my best use the whole part of the beast.

JJ: Cubs: for real. Their run differential is the best in all of baseball by a wide margin, and I don't see any of the other NL Central teams being able to hang with them. I think the big questions are whether Rich Hill rediscovers his control and returns to the rotation, and whether Kerry Wood can hold up as the team's closer. Barring injuries, I think they'll be OK, and even with those injuries, they have a bit of depth to either cover from within or make a trade to help themselves out.

Andruw: lots of questions about him today. The upside of his injury is that it may explain some of his struggles, it may force him to get back in shape as he rehabs, and it will give Dodger fans a bit of relief when it comes to the daily drama of the outfield lineup.

Torre: Furcal being hurt certainly takes a bite out of that lineup. But really, Torre's going to have to get over this Russell Martin-at-3B fetish, even though it's only been a total of 37 innings he's played there. It's fine to give him a breather now and then, but when you're stealing at-bats from DeWitt or LaRoche to give them to Gary Bennett, something is definitely wrong.

jlebeck66 (WI): Dodgers. DeWitt. LaRoche. How's this gonna end? Did LaRoche anger a deity or something?

JJ: Sticking with this topic for a moment, I'm as big a LaRoche booster as you'll find, but DeWitt is knocking the stuffing out of the ball. I don't expect that to continue unabated, but there's no sense in sitting him down right now.

From a long-term standpoint, it's a nice problem to have. I'd hate to see them trade LaRoche, but I don't think they necessarily have to. I wonder whether the Dodgers would consider revisiting the DeWitt-to-second experiment that they tried in 2006, when the kid was at Vero Beach. With Jeff Kent clearly showing his age and Tony Abreu apparently joining the Federal Witness Protection program, that may be a palatable option.

Joe (Tewksbury, MA): Why do I keep reading about how much trouble the Yankees are in? Hasn't this been the story for three years running now? Slow start, fast finish. Do you see anything to make you think this year will be different from 2005-2007?

JJ: Yes. Everybody in the lineup, including Alex Rodriguez and Jorge Posada is a year older, and with the exception of Melky Cabrera and Robinson Cano, they're a year further away from their statistical primes, to say nothing about the fact that Cano looks pretty lost right now. The bench is weak even for a team that's done poorly in that area in the recent past. Seriously, I'd take Chili Davis, Darryl Strawberry, Luis Sojo and Ron Coomer circa 2008 over some of the stiffs they have lying around.

There's that, plus a weak pitching staff where the back of the rotation has been a thorough disaster thus far and the bullpen situation is considered so fragile that there's actually a question about whether they'll move Joba Chamberlain to a starting role this year. Add to that the fact that the AL East has gotten tougher and I think there's no longer any guarantee that the Yankees will contend, let alone win the division.

The other thing in play is the new manager. Through the early season debacles of the last few years, Torre was able to absorb the front office's slings and arrows and still give off a sense of calm confidence that things would eventually turn around. Girardi is protected from the barbs of Hank Steinbrenner at the moment -- his focus appears to be on forcing Brian Cashman out -- but Little Joe is the kind of guy who seems more likely to go Billy Martin bonkers as things get worse, and I don't think that's going to help.

Labels: chat, Dodgers, JAWS, Joe Torre, radio, Unfiltered, Yankees

Tuesday, May 20, 2008

Return of the Chatterbox

Labels: chat

Monday, May 19, 2008

Somebody Get Me a Dock...

Ellis had a few big years pitching for the Pittsburgh Pirates, notably in 1971, when he went 19-9 with a 3.06 ERA for a team that would win the World Series. That was the only season in which he made the All-Star team or received Cy Young consideration (he finished a distant fourth behind Fergie Jenkins, Tom Seaver and Al Downing), but he was a solid, intimidating pitcher who won 138 games in the majors and a key hurler on five division winners over the course of his 12-year career. He's got a few other claims to fame:

• On June 12, 1970, Ellis pitched a no-hitter while purportedly under the influence of LSD. He walked eight batters and hit one.

• In the summer of 1971, Ellis was named to the NL All-Star team. With Vida Blue set to start for the AL, Ellis declared that there was no way NL manager Sparky Anderson would dare start him to create a matchup of two black pitchers. Wrote Kevin McAlester in a lengthy, worthwile profile for The Dallas Observer in 2005: "This launched the inevitable national sportswriters' debate about how racism didn't exist in 1971, and how dare he and why would he and so on and whatnot. The flap had its intended effect: Anderson, grumblingly, started Ellis, and the pitcher soon became one of the most reviled players in the league, branded a troublemaker and miscreant." Ellis received a letter of praise from Jackie Robinson following the incident.

• On September 1, 1971, Ellis took the field as the starting pitcher for the first all-black lineup in major league history. It wasn't one of Ellis' better outings; he was knocked out in the second but the Pirates came back to win 10-7.

• In 1973, following a profile in Ebony magazine on his hairstyle, Ellis took the field for a pregame workout wearing hair curlers, a move that drew the wrath of stuffed shirt Bowie Kuhn. Said curlers were donated to the Baseball Reliquary upon Ellis' induction into the iconoclastic museum's Shrine of the Eternals in 1999.

• On May 1, 1974, attempting to light a fire under his team, the Pirates, Ellis drilled the first three Reds' hitters to come to the plate. Pete Rose, the first batter, actually rolled the ball back to Ellis upon being hit. Joe Morgan got plunked, as did Dan Driessen. Tony Perez was nearly hit as well; he walked. Finally, with a 2-0 count on Johnny Bench, Ellis was pulled by manager Danny Murtaugh. Bronx Banter has an excerpt of the story behind this from Ellis' entertaining biography, Dock Ellis in the Country of Baseball

• In December 1975, Ellis was traded by the Pirates to the Yankees for pitcher (and real-life MD) Doc Medich. Also in the deal was a second base prospect named Willie Randolph. Ellis would go 17-8 with a 3.19 ERA during his only full season with the Yankees, helping them to their first pennant since 1964. Randolph took over the starting slot at the keystone and hit .267/.356/.328 while stealing 37 bases. The deal, engineered by Yankee GM Gabe Paul, ranks among the best in Yankees' history.

After being traded by the Yankees -- to Oakland, in a deal for Mike Torrez -- early in 1977, Ellis bounced around to Texas and the Mets before finishing his career with a few more games as a Pirate in late 1979. They would again go on to win the World Series, though he played no part in that. Drug and alcohol problems had hastened Ellis' departure from the majors -- he later said he never pitched a game without the aid of amphetamines -- but upon leaving baseball, Ellis checked into a rehab facility and cleaned up. He went on to become a drug counselor.

Back in 1993, a band called the SF Seals, led by baseball fan Barbara Manning, released a three-song EP on Matador Records (run by Can't Stop the Bleeding domo Gerard Cosloy). Two songs were covers, one devoted to Denny McLain, the other to Joe DiMaggio. The sole original "Dock Ellis," is a chugging psychedelic rock number memorializing some of the pitcher's signature moments. Rock out to Dock and spare a moment for him in your thoughts today.

Labels: baseball history, music

Sunday, May 18, 2008

The Subpar Subway Series and Its Sub Rosa Subplots

Continuing their middling ways, the Mezzo-Metsos haven't strung together more than two wins or losses together all month, but if there's one thing Mets fans can be unequivocal about this year (other than a general "You suck!" that may as well become their rallying cry), it's that thus far the team's controversial deal with the Nationals is paying off. While Lastings Milledge is hitting just .238/.309/.327 with a -0.6 VORP for the Nationals, Ryan Church is hitting .310/.378/.538 with a team-high 14.0 VORP for the Mets, with Brian Schneider (.318/.385/.400) adding another 4.8 VORP. If only those two guys would grow cornrows...Not pictured in the Mets' entry are the events following the aftermath of Thursday afternoon's loss, when closer Billy Wagner ripped his teammates, particularly Carlos Delgado, for not being around to talk to the media after the game, an event which spurred a team meeting and fueled speculation that manager Willie Randolph's job is on the line. Though Wagner apologized to Delgado, it's clear he's become a go-to guy in the team's unhappy clubhouse, the heir apparent to garbageman/closer John Franco; recently he ripped Oliver Perez as well.

Yammering Hank: In a further attempt to prove himself the measure of his old man, the old Boss, the Yankees' new boss compares his team unfavorably to the Rays as the latter holds the Yanks to six runs in a four-game series which knocks the pinstripes into last place in the AL East--the latest in a season that the team has been in the cellar since 1995. The outburst places pending free agent Brian Cashman directly in the crosshairs just as the team prepares to face Johan Santana in the Subway Series. Not helping matters is Ian Kennedy's return from the minors to deliver more of the same; he has just one quality start out of seven.

The Mets did have the advantage of throwing Johan Santana against the Yanks on Saturday, rubbing salt in a wound that may well lead to Cashman's departure at the end of the year. Santana, who even before the rainout had already been pushed back a day in order to set up this marquee matchup, didn't pitch particularly well, surrendering four runs and three homers in 7.2 innings, but one bad inning from Andy Pettitte and another from Kyle Suckass Farnsworth were enough to make the performance stand up. Santana has now allowed 11 homers in 60 innings this year, a rate of 1.65 per nine. That's even higher than last year's career-worst 1.36 per nine; adjusted for park and league levels via Baseball Prospectus' translated stats, it's 28 percent worse. Still, he's 5-2 with a 3.30 ERA and 8.6 strikeouts per nine innings, a performance that would look pretty nifty if it were done in Yankee pinstripes.

Thus this past week has served as a bitter reminder of the risk Cashman took by not trading for the two-time Cy Young winner. With Yankee youngsters Kennedy and Philip Hughes, the two pitchers who figured prominently in the team's negotiations with the Twins, nursing a combined record of 0-7 with an 8.70 ERA and the latter on the DL until July due to a stress fracture in his rib, the grass is greener on the other side of the Yankees' fence. Never mind the fact that Melky Cabrera, who would likely have been traded to the Twins, had until recently been one of the team's most productive hitters (a 7-for-38 slump with two walks and just one extra-base hit has cooled him off). The impossible expectation of manchild Hank is not only for the team to win while rebuilding, it's to do so without acknowledging the conflicting priorities if not the logical impossiblity of having one's cake and eating it too.

With Kennedy sputtering in his return from the minors, the day when Joba Chamberlain shifts to the rotation probably isn't far off, despite the cryptic signals from Cashman and manager Joe Girardi. Chamberlain has now thrown 18.1 innings in relief. If he were to somehow be able to move to the rotation by the end of this month, he'd probably have 21 starts left (Chien-Ming Wang and Andy Pettite both have nine, and in a five-man rotation each slot averages 32 turns). At an average of six innings per start, that's 132 innings, plus his 18.1 is 150.1, only five above his Rule of 30-based estimate of 145 innings. At the outset of the season, I estimated that Chamberlain would pitch three months on a 90-inning reliever pace and three on a 180-inning starter pace, but the Yankees' dearth of leads to protect has put him on something closer to a 65-inning reliever pace and thus bought him more starts down the road.

The bottom line, I think, is that there's a lot of misdirection coming from the Yankee brass in an attempt to disguise the fact that if Kennedy doesn't get his shit together over the course of the next two starts -- the end of this month, basically -- the time to move Joba will be upon the Yankees. When that point arrives, it will be second-guessed to high heaven as something that should have been done a long time ago. But the reality is that if the team wants to stick to a realistic workload that won't endanger Chamberlain's future -- and here I'm omitting a whole debate as to whether the current limits are correctly optimizing the usage of young pitchers relative to their injury risk -- they probably couldn't have sped up the timetable by much and still hoped to have him available as a starter down the stretch.

I'm fond of quoting the famous Leo Durocher line, "You don't save a pitcher for tomorrow. Tomorrow it might rain," but that balancing act with regards to the value of this precious resource is the cornerstone of the otherwise the impossible dream of rebuilding while winning. The bullpen may suffer a bit due to Chamberlain's absence from the setup role, but it will be the right decision at the right time for the team's best interests, and the player's as well.

Labels: Hit List, Mets, Yankees

Wednesday, May 14, 2008

Last Buzz

The 1962 and 1963 teams had overachieved; the former (102-63) had outdone their Pythagorean record by five games, the latter (99-63) by seven games. Their luck finally reversed in 1964. Despite outscoring opponents by 42 runs with virtually the same cast, the Dodgers slumped to sixth at 80-82, six games below their projected record. Losing Koufax for the final six weeks of the season didn't help, but the Dodgers were just 58-57 and mired in seventh place when he went down with traumatic arthritis, the result of a jammed shoulder sustained while diving to avoid a pickoff throw.Reviewing Bavasi's life's work, I find it remarkable and more than a little disappointing that he's not in the Hall of Fame, but then general managers haven't been well-served by Cooperstown (more on that in a moment). Bavasi has been up for election by the Veterans Committee in each of the past two years, but VC politics and the change from a larger electorate of all living Hall of Famers, Spink and Frick award recipients to a 12-man panel of so-called experts did not serve him well. After pulling 37 percent in 2007, he fell to under 25 percent (with no exact total given) in 2008. In the first year, the candidates were on a composite ballot with managers and umpires, and the electorate could vote for as many as 10 individuals, while in 2008, the group of 12 could only vote for as many as four individuals:

Koufax and Don Drysdale had combined for 68 starts of 2.01 ERA ball, amazing even given that the park-adjusted league average for Dodger Stadium was 3.25. The rest of the 1964 rotation, most notably Phil Ortega and Joe Moeller (25 and 24 starts, respectively), had combined for a 3.96 ERA, nearly double that of the dynamic duo. Thus Bavasi's big focus over the winter of 1964-1965 was bolstering the rotation, and to do so he made perhaps the boldest move of his tenure, trading the team's top power threat, Frank Howard, to the Washington Senators in a seven-player deal. A 28-year-old, 6-foot-7 behemoth, Howard had hit 24 homers in 1964, but those only partially redeemed a .226/.303/.432 performance coupled with defense that was well below average (-13 runs according to the Davenport Translations, and worth only 2.8 WARP in all). Howard would go on to some monster years in Washington, but Claude Osteen, the 25-year-old lefty who was the prize of the return package, would become a mainstay in LA. In 1965, his 15-15 record belied the impact of giving the Dodgers 40 starts of 2.79 ERA ball in an environment where 3.26 was average.

To offset the loss of Howard, first baseman Ron Fairly moved to right field, and Wes Parker, who'd spent 1964 as a reserve, moved in at first. Though hardly a power threat, Parker was a legitimate plus defender who would go on to win six Gold Gloves. Also new to the lineup was second baseman Jim Lefebvre, who won Rookie of the Year honors while upgrading a position where Nate Oliver, Dick Tracewski, and Jim Gilliam had combined to hit an anemic .235/.308/.283 the year before. Along with Maury Wills and Gilliam--who had retired to become the team's third-base coach, only to rejoin the lineup as the third baseman in late May--the infield was entirely composed of switch hitters, a first.

Bavasi needed to make one more major move once the season began. On May 1, two-time All-Star Tommy Davis, the team's left fielder, broke his ankle sliding into second base; though Davis was coming off of a down year (.275/.311/.397, 5.9 WARP), the loss looked potentially devastating to the lineup. Luckily, Bavasi had stashed Lou Johnson at Triple-A Spokane; Johnson was a 30-year-old journeyman who had been kicking around the minor leagues for a dozen years while getting just 185 big league at-bats; he'd been acquired from the Tigers for pitcher Larry Sherry the year before. Johnson filled in seamlessly for Davis, hitting .259/.315/.391 and tying with Lefebvre for the team high in homers with 12 (no, those Dodgers didn't have much offense, but remember, it was a low-offense era). All in all, his performance was worth 5.0 WARP, right in line with a conservative estimate of what Davis might have provided.

The Dodgers led the NL for most of the year before a 13-16 stretch starting in mid-August dropped them as far down as third behind the Giants and Reds. They stormed back and won 13 straight, with the pitching staff allowing just 14 runs in that span, six of them in one game. They retook first with a week to play, nipped the Giants by two games to win the pennant, and went on to win a thrilling seven-game World Series over the Minnesota Twins, with Koufax pitching a three-hit shutout on two days' rest in the clincher. Johnson homered to provide the finale's first run; it was his second homer of the series as he hit .296/.321/.593. For the second time in three years, the Dodgers were World Champs.

2007 2008Nobody from this august group was elected by the larger VC in 2007, and of the three elected in 2008, only O'Malley had even drawn minimal support beforehand. Meanwhile Marvin Miller was knocked down a peg by the reconstituted group in favor of stuffed shirt Kuhn. Interestingly, though Bavasi's take on the entry of agents and free agency into the game was a somewhat reactionary one, he himself harbored no ill will against Miller ("Marvin Miller never did one thing to hurt the game of baseball," he told BizofBaseball.com's Maury Brown).

Barney Dreyfuss ---- 83.3%*

Bowie Kuhn 17.3% 83.3%*

Walter O'Malley 44.4% 75.0%*

Ewing Kauffman ---- 41.7%

John Fetzer ---- 33.3%

Marvin Miller 63.0% 25.0%

Bob Howsam ---- 25.0%

Buzzie Bavasi 37.0% <25.0%

Gabe Paul 12.3% <25.0%

John McHale ---- <25.0%

Bill White 29.6% ----

August Busch Jr. 16.0% ----

Charley O. Finley 12.3% ----

Phil Wrigley 11.1% ----

Author and former Hall of Fame employee Bruce Markusen had this to say about Bavasi's case upon his passing:

Perhaps Bavasi has been overlooked because of those who worked with him--and before him--with the Dodgers. His predecessor as Dodgers GM was Branch Rickey, one of the game's clearest thinkers, the man who brought Jackie Robinson to the big leagues, and a certifiable baseball genius. That's a tough act to follow, though Bavasi did it very well. And then there was Bavasi's owner during his time with the Dodgers. Walter O'Malley, the National League's most influential owner for decades, cast a long shadow as a mover and shaker. O'Malley himself didn't earn election to the Hall of Fame until last December, so perhaps it's understandable that Bavasi has had to wait this long.Unfortunately it won't be until 2010 that Bavasi can be considered again, but then again, we shouldn't expect much from the Veterans Committee in any form.

There's another factor at work here, too. In general, general managers are woefully underrepresented in the Hall of Fame. Unless they happened to have doubled as owners, their chances of making the grade in Cooperstown haven't been very strong. Look at some of the men who have been elected to the Hall of Fame at least in part for their work as de facto general managers. Rickey was, for a time, the Dodgers' owner, Lee MacPhail worked for a long time as the American League president, Ed Barrow was an owner, and Bill Veeck was an owner. As fellow historian Eric Enders has pointed out, only George Weiss has been elected to the Hall of Fame solely for his work as a GM. Weiss was never an owner, never a league president, and never a pioneer in the sense of Rickey.

Well, it's time to change that trend. General managers are vitally important to building championship ballclubs. The best ones should be represented in Cooperstown. Bob Howsam, the architect of the Big Red Machine who died earlier this year, should be in, as should Bavasi. Arguments could also be made for Harry Dalton (based on his work in Baltimore) and perhaps even Joe Brown (the architect of two championship teams in Pittsburgh). And perhaps one day John Schuerholz, the longtime general manager of the Braves, will receive his due in the form of a plaque in the Hall of Fame Gallery.

We can only hope that the same honor is given to Bavasi, even if it has to come after he can enjoy it.

Labels: baseball history, Dodgers, Hit and Run

Saturday, May 10, 2008

Walking the Line

This Is How the Other Half Lives? Last year the Yankees claimed four of the league's top 20 hitters according to VORP, but with Alex Rodriguez and Jorge Posada sidelined and Derek Jeter and Robinson Cano struggling, things just aren't the same; since the first two went on the DL, the team is scoring just 4.22 runs per game. Jeter (.301/.331/.374) has yet to homer and has walked just four times in 131 PA, while Cano (.172/.226/.297) has been mired below the Mendoza Line all season long, as has Jason Giambi (.163/.324/.419).Jeter finally homered on Saturday in the Yankees 38th game of the year, the longest he's gone without a dinger to start the year save for 2003, when he injured himself on Opening Day and missed 36 games. In 2001, he also hit his first homer on May 10, but that was in the Yanks' 35th game. Giambi homered on Friday night and doubled on Saturday; he dug himself an early hole but since I took a look at his performance a few weeks back he's actually hitting .255/.383/.660. I have to admit, that's better than I thought.

Anyway, one recurrent theme in this week's Hit List, which was titled "Walking a Fine Line," was pitcher strikeout to walk ratios. I needn't remind you of Cliff Lee, who shut down the Yanks last week and now has a 39/2 K/BB ratio which suggests the dude is, well, In the Zone. Fausto Carmona, whom the Yanks dinged the night before, only to lose when Joba Chamberlain surrendered a three-run, pinch-homer to David Friggin' Dellucci (a game I attended and found little reason to discuss here, such was my disgust), has a 15/31 K/BB ratio, more than twice as many walks as strikeouts. Elsewhere around the league, pitchers as diverse as Scott Olson, Gavin Floyd, Daisuke Matsuzaka, Justin Verlander and Saturday's Yankee victim Jeremy Bonderman (3 K, 4 BB to run his line to 25/29 for the year) are having similar issues, some of them succeeding in spite of those strike zone woes, others (particularly those Tigers) not so much.

As much as statheads harp on K/BB ratios for pitchers, not all ugly ratios are created equal, some are the symptoms of wildness or bad mechanics, others may be a byproduct of good situational pitching -- combined with some extra luck in the Batting Average on Balls in Play department -- over a small sample size. Anyway, the topic was one I spent a good portion of Friday's XM Radio appearance on the Rotowire Fantasy Sports Hour discussing with Chris Liss. You can hear the conversation here.

Labels: Hit List, radio, Yankees

Wednesday, May 07, 2008

Bavasi and the Bookshelf

By this time, the core of the team that Branch Rickey had assembled was aging. [Jackie] Robinson retired rather than report to the Giants after a 1956 trade. The 1957 season was soured by the team's inevitable departure for Los Angeles (a topic recently revisited here by Gary Gillete), while the Boys of Summer crept closer to their ruin. [Roy] Campanella was paralyzed in a January 1958 auto accident, [Don] Newcombe was traded to Cincinnati after an 0-6 start, and Pee Wee Reese became a part-timer. The Dodgers finished seventh out of eight teams at 71-83 in their inaugural season in LA, their first sub-.500 campaign since 1944. Yet Bavasi was already working to rebuild his aging ballclub by remaining true to a pair of Rickey principles: a commitment to the Dodgers' player development system, and complete faith in the virtues of power pitching. He assembled an unlikely World Champion in 1959 out of that mess, one that -- prior to the dawn of the Wild Card era -- Bill James called the weakest of all time.Part Two will run next week.

Bavasi was able to rely on the nearly overripe fruits of the system to overhaul the team. [Johnny] Roseboro and [Charlie] Neal, both of whom had spent the better part of the decade in the minors, stepped into the lineup as solid regulars in 1958; Neal enjoyed a breakout year in 1959, when he was the league's top-hitting second baseman via a .287/.334/.464 performance with 19 homers and 17 steals. The speedy [Maury] Wills, who had toiled for nine years in the minors, was recalled midway through 1959, replacing a slumping Don Zimmer at shortstop, and hit a sizzling .345/.382/405 in September. Bavasi also made one key trade that year, acquiring left fielder Wally Moon from the Cardinals for Gino Cimoli. The lefty-swinging Moon rebounded from an off year with St. Louis by taking advantage of his odd new environment, the Los Angeles Coliseum. Built in 1923 for University of Southern California football games, the Coliseum was a 93,000-seat football stadium ill-suited for baseball. It was 300 feet down the right field line, 440 to right center (reduced to 375 in 1959), 420 to dead center, and just 251 feet down the left field line (which was topped by a 40-foot screen). Moon quickly learned to focus on hitting to the opposite field; 14 of his 19 home runs were at home, nine of them "Moon Shots" which went over the screen.

The Dodgers used another of their new home's quirks -- dim lighting and a major league-record 63 night games -- to give their pitching staff an added advantage. The team had already led the league in strikeouts every year since 1948, but in 1959 they became the first staff to top 1,000 in a season, blowing away 1,077 hitters. Don Drysdale led the league with 242, while Sandy Koufax placed third with 173 despite tossing just 153 1/3 innings. Johnny Podres, the hero of the 1955 World Series, was seventh with 145 and third in strikeout rate. Koufax and Drysdale had been signed by the Dodgers in 1954; the former, a bonus baby, had joined the big club in 1955 but had struggled with the strike zone ever since, while the latter joined the staff the following year and became a rotation mainstay in 1957. The duo would anchor the team's fate for the better part of the next decade.

Further aided by another pair of pitchers Bavasi promoted in midseason -- veteran Roger Craig and rookie Larry Sherry -- the Dodgers won a three-way race in 1959, outlasting the Giants (now relocated to San Francisco) and the Milwaukee Braves, whom they beat in a best-of-three playoff at the end of the season (for more on that race, see my chapter in It Ain't Over: the Baseball Prospectus Pennant Race Book, now out in paperback). They then beat the Go-Go Chicago White Sox in the World Series

They reverted to fourth place the following year, and finished second in 1961 despite holding the lead as late as August 15. They finally moved into state-of-the-art Dodger Stadium in 1962, a ballpark that dramatically favored pitchers, and won 102 games, the second-highest total of the Bavasi era. Sparked by the speedy Wills, who stole an NL record 104 bases, a new stable of homegrown youngsters, including first baseman Ron Fairly and outfielders Willie Davis, Tommy Davis (no relation), and Frank Howard, helped them finish second in the league in runs scored despite the park's suppression of offense. Drysdale and Koufax both topped 200 strikeouts, with the former leading the league for the third time in four years and winning the Cy Young on the strength of a 25-9 record, and the latter topping the circuit in ERA despite a two-month absence.

Unfortunately for the Dodgers, the Giants won 103 games, including the rubber match of a three-game playoff. That game almost cost Bavasi and Alston their jobs. Alston, forever working on one-year contracts, had been forced to swallow the irascible Leo Durocher as part of his coaching staff -- "on the grounds that we don't want bridge partners or cronies for assistants," explained O'Malley -- and the Lip continually undermined the manager in front of the team and second-guessed him in the press, particularly over Alston's staying with Stan Williams instead of summoning Drysdale amid a four-run ninth-inning meltdown in the deciding game of the playoff. Soon after the defeat, Durocher carped that the team would have won if he'd been in charge. Bavasi hit the roof when he found out, threatening to fire Durocher, but was overruled by O'Malley, who wanted to fire Alston in favor of Durocher. Bavasi told O'Malley, "If you fire Alston, I'm gone too. He didn't make those errors, he didn't give up those base hits. How in the hell can you say it was Alston's fault?" O'Malley backed down, and all three men kept their jobs.

• • •

In my thirst for insight into Bavasi's days with the Dodgers, I've been plowing through my latest find from Manhattan's awesome Strand bookstore (which boasts 18 miles of books on its shelves the way McDonalds boasts of billions served), Harold Parrott's The Lords of Baseball

On that note, one of the occupational hazards of palling around with other baseball writers is that your reading list is always growing. My head is currently reeling from suggestions gathered this past Monday, when I met up with Kevin Baker, Alex Belth, Steven Goldman, Derek Jacques, Joe Sheehan and Emma Span to quaff a few beers and attend a reading for The Anatomy of Baseball

1. Ball Four by Jim Bouton -- the groundbreaking look behind the curtain at the ups and downs of a baseball playerEven personally speaking, I'd be hard pressed to call this list my definitive one; at the time I was just ticked off enough at Bill James to avoid fretting over whether or not to include Whatever Happened to the Hall of Fame?, The Bill James Guide to Managers, the Historical Abstract, or This Time Let's Not Eat the Bones. Given a second batch of ten to right that wrong, I'd also add Weaver on Strategy, my Baseball Prospectus colleagues' Baseball Between the Numbers, Moneyball, Nine Innings, Red Smith on Baseball, and the aforementioned Veeck as in Wreck, and that would still leave me bummed that I couldn't include another batch of Roger Angell, a shout for the idiosyncratic, Bouton-edited anthology "I Managed Good But Boy Did They Play Bad", a nod for Pat Jordan's A False Spring, a giggle for The Bronx Zoo, and a self-interested plug for It Ain't Over.

2. Boys of Summer by Roger Kahn -- a meditation on mortality and a brilliant, poignant study of the flawed beauty of the human organism, masquerading as a baseball book

3. The Summer Game by Roger Angell -- a lyrical account of baseball in the Sixties as seen through the eyes of one erudite fan

4. Seasons in Hell by Mike Shropshire -- for my money, this gonzo account of the 1973-1975 Texas Rangers is funniest baseball book of all time

5. Nice Guys Finish Last by Leo Durocher and Ed Linn -- an agonizing choice between this and Veeck as in Wreck, ultimately decided by Leo the Lip's role in the New York-centric golden age in the Forties and Fifties

6. Past Time: Baseball as History by Jules Tygiel -- a concise summary of nine trends that changed baseball, by one of the game's unsung scholars

7. Lords of the Realm by John Helyar -- an often hilarious account of a century's worth of labor versus management battles

8. The Glory of their Times by Lawrence Ritter -- the classic oral history of early 20th century baseball

9. The Great American Baseball Card Flipping, Trading, and Bubble Gum Book by Brendan C. Boyd and Fred C. Harris -- two fans explore their love affair with those cardboard slabs and the memories they represent

10. The Numbers Game by Alan Schwarz -- a wonderful exploration of the history baseball statistics, from the development of the box score to the onslaught of real-time Internet updates to the entry of performance analysis into front offices

The fun part is that such lists offer expert recommendations and the occasional gentle nudge. Alex came over to watch the Yankees game last Friday night, and he quizzed me on two books with which he wasn't familiar, Eliot Asinof's Man on Spikes and Boyd and Harris' The Great American Baseball Card Flipping, Trading and Bubble Gum Book. The former, a novel by the man who wrote Eight Men Out (seen the movie several times, never read the book) is one that's been sitting on my shelf unread for a couple of years save for its first half-dozen pages (just enough to get me to take it home), while the latter has probably provided me with as much inspiration and as many laughs as Ball Four or Bill James. As such, I was surprised that Alex was unfamiliar with the authors' blend of irreverence and nostalgia, for it's one that really has found a home in the blogosphere and beyond, particularly via Alex's own Baseball Toaster colleague, Josh Wilker, the books's most worthy literary heir who writes that it "not only celebrates the magic of baseball cards but gives voice to everyone who ever collected them."

For myself, the list has shamed me into swearing that Man on Spikes, Dollar Sign on the Muscle and a few others already on my shelf will get their day. But not before I finish reading The Lords of Baseball, that's for damn sure.

Labels: baseball history, books

Saturday, May 03, 2008

Farewell to a Much Better Buzz

--Buzzie Bavasi (1914-2008)

While Buzz Bissinger continues to be raked over the coals, the baseball world lost one of its titans on Thursday, as longtime executive Buzzie Bavasi died at age 92. The old-school Bavasi is best remembered as the architect of four World Champion Dodgers teams and eight pennant winners (1952, '53, '55, '56, '59, '63, '65, '66, champions in bold), serving as the team's general manager from late 1950 (when he took over from Branch Rickey) to mid-1968, a period encompassing the franchise's transcontinental shift from Brooklyn to Los Angeles, their longest run of success and their days as the National League's predominant powerhouse.

Bavasi's accomplishments weren't limited to that span, however. He joined the Dodger organization in 1938, and worked in their farm system until 1943, stepping aside to serve in the Army during World War II. When he returned he played a key role in the game's integration: in 1946, as Jackie Robinson was smashing through organized baseball's color barrier in Montreal, Bavasi took the fight to American soil, running the Dodgers' Class B Nashua affiliate, which featured Roy Campanella and Don Newcombe and was skippered by Walter Alston. As the Los Angeles Times' obituary recounts:

"I'll never forget one night in Lynn, Mass.," Campanella said in 1983. "Newcombe had pitched, and I hit a home run, and we won the game. We were all dressed and sitting in the bus. Buzzie said he was going inside to pick up the check. All of a sudden, we heard Buzzie and their manager fighting. We went in and broke it up. We found out later that their manager" had used a racial slur when he told Bavasi, " 'Without those two [black players], you wouldn't have won.' Buzzie went after him."In 1947, he was summoned to work for the Dodgers, and one of his duties was to scout the Vero Beach Army base that became Dodgertown and hammer out an agreement with the city. Bavasi then spent three years as the Montreal Royals' GM before being named to the Dodger post in late 1950. As the club's GM, he was well known for both his tight purse strings and his paternal attitude towards players:

I always had a warm feeling of gratitude toward Buzzie because he took a chance on bringing me up from the minors after eight years. He stuck by me," former Dodgers shortstop Maury Wills said Thursday. "He had a way of getting me to play hard without paying me a lot of money."Bavasi took pride in his ability to operate on a budget, but as the Dodgers' success took its toll on their payroll, he met something of a personal Waterloo when he presided over the dual holdout of Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale in the spring of 1966, a year which wound up being the final season of Koufax's career and the Dodgers' last pennant until 1974. As Bavasi recounted in Sports Illustrated in 1967:

One of Bavasi's favorite ploys was to draw up a phony contract in the name of a player coming off an excellent season and type in an artificially low salary. When another player who wasn't as good came into his office to negotiate, Bavasi would leave the phony contract on his desk, then excuse himself from the room. The player inevitably would take a peek at the contract, read the low-ball salary and back down in his own negotiations when Bavasi would return to the room.

To tell the truth, I wasn't too successful in the famous Koufax-Drysdale double holdout in 1966. I mean, when the smoke had cleared they stood together on the battlefield with $235,000 between them, and I stood there With a blood-stained cashbox. Well, they had a gimmick and it worked; I'm not denying it. They said that one wouldn't sign unless the other signed. Since one of the two was the greatest pitcher I've ever seen (and possibly the greatest anybody has ever seen), the gimmick worked. But be sure to stick around for the fun the next time somebody tries that gimmick. I don't care if the whole infield comes in as a package; the next year the whole infield will be wondering what it is doing playing for the Nankai Hawks.Full of more than a little bravado, the four-part series offers a revealing window into the tactics of a Reserve Clause-era executive so smug about holding the best cards in the negotiation game that he could afford to lay them on the table for the world to see. These fascinating articles -- first brought to my attention by Alex Belth, who dug them out of the SI clip library for me a couple years back -- are now fully available online via the recently debuted SI Vault :

...The double holdout started on February 26, 1966, when spring training opened and Sandy and Donald didn't show. It looked in the papers as though they had made a big salary demand on the club and the club had turned them down. But it wasn't that simple. Being three good friends, as I hope we still are, Donald and Sandy and I had met and talked things over. In the first meeting, right after the 1965 season, we got no place. We sat down in my office at Dodger stadium and they said they had an agent—Sandy's lawyer, Bill Hayes—and that they wanted a three-year no-cut contract totaling $1 million and that neither one would sign unless both were satisfied. I told them I would negotiate only with them, that any discussions they had with their agent were their own business but please keep him away from me, that the amount of money they were asking was ridiculous, and that nobody on the ball club, including me and Walter Alston, was ever going to get more than a one-year contract. As I recall, I said something like, "You're both athletes, and what you're selling is your physical ability, and how can you guarantee your physical ability three years in advance? If you guarantee me that you will both be healthy and strong and still winning 20 games each in 1968, I'll give you a three-year contract." Since not even Cassius Clay could make a guarantee like that, the meeting broke up. But there was plenty of time; this was only October, the World Series was barely over and I was in no rush to get them signed, especially at their asking price of $166,000 per year apiece. From the beginning I was willing to give them raises on their 1965 salary, which were $80,000 for Don and $85,000 for Sandy. I had it penciled into my budget: $100,000, more or less, for Sandy, and $90,000, more or less, for Donald.

...The double holdout was over, but I can't say that I felt good about it. We wound up giving the boys much more money than we had intended, and if you had to pick a winner in the whole argument, you'd have to say it was Drysdale and Koufax. Donald got a $30,000 raise and Sandy got a $40,000 raise, and neither would have commanded that much money negotiating alone. After all, they got the biggest raises in baseball history. To that extent, the double holdout worked, although they gave in on the three-year contract for $1 million, which I don't think they ever meant, anyway. But, as I said before, the plan only worked because the greatest pitcher in baseball was in on it, and also they caught us by surprise. Believe me, Walter O'Malley and I have talked the problem over many times, and no double holdout will ever work again on the Los Angeles Dodgers. We're firm on that. The next time two of them come walking in together, they'll go walking out together. Koufax and Drysdale took advantage of a good thing, that's one way to look at it, and another way to look at it is, why shouldn't they? All's fair in negotiating, as I have also said before. This was a unique situation, and it will never happen again.

Anyway, the double holdout didn't cost the ball club quite as much as the figures would seem to indicate. In the first place, I had anticipated the possibility of having to come up with high figures for Don and Sandy, especially after the season they had had, and therefore I had not been quite as generous with some of the other players as I might have been. I don't mean I cut anybody just to get money to pay the two pitchers. It worked more like this: let's say a kid comes into my office and I've got him penciled in for $27,000, and he sits down and says that he wants $23,000. This happens all the time, believe me, and my natural inclination is to say, "I've got you down for $27,000, and that's what you are going to get." But not this time. This time if the kid said he'd sign for $23,000 I'd let it go at that, or maybe I'd sign him for a thousand more. The net result was that our 1966 budget for ballplayers went up exactly the $100,000 I had planned on, with Koufax and Drysdale getting $70,000 of the increase and the other 24 guys getting the rest. I'd have liked to give the other players more, but a budget is a budget and I stuck to it.

• May 15, 1967: The Great Holdout

• May 22, 1967: Money Makes the Player Go

• May 29, 1967: They May Have Been A Headache But They Never Were A Bore

• June 5, 1967: The Real Secret Of Trading

After 1968, Bavasi left the Dodgers for the expansion San Diego Padres, where he served as team president and part-owner, but he couldn't replicate his success, as the team finished in the NL West cellar for its first six years. The Padres' fate improved in 1975, as they escaped the basement for the first time, but Bavasi clashed with new owner Ray Kroc and left following the 1977 season.

Angels owner Gene Autry soon hired him to be his team's executive vice president, and Bavasi oversaw their first division championship in 1979, an accomplishment that was dimmed by the acrimonious departure of Nolan Ryan following the season. The Angels won the AL West again on Bavasi's watch in 1982, but although he signed big-name free agents such as Don Baylor, Rod Carew, Bobby Grich, Reggie Jackson and Fred Lynn, he struggled to adjust to the GM's loss of leverage in the post-Reserve Clause era, traded far too much of the Angels' young talent (Willie Mays Aikens, Tom Brunansky, Brian Harper, Carney Lansford, Rance Mulliniks, Dickie Thon...) and retired in 1984. Two of his sons, Peter and Bill, became GMs at the major league level, though neither has come close to filling their father's shoes; the latter is currently the Seattle Mariners' GM.

Bavasi remained lucid and communicative well into his later years; both Biz of Baseball domo Maury Brown and New York Times columnist Dave Anderson recount their correspondences with him in recent articles. The Times also carries the inevitable obit, and there's another worthwhile one over at MLB.com.